Efficiently Planning Stable Object Placements

A fast, general, and physically-grounded method to stable placement planning

From our paper:

Stable Object Placement Planning from Contact Point Robustness

By Philippe Nadeau and Jonathan Kelly

In IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2025

🔗 Paper 🔗 Video

Abstract

We introduce a planner designed to guide robot manipulators in stably placing objects within intricate scenes. Our proposed method reverses the traditional approach to object placement: our planner selects contact points first and then determines a placement pose that solicits the selected points. This is instead of sampling poses, identifying contact points, and evaluating pose quality. Our algorithm facilitates stability-aware object placement planning, imposing no restrictions on object shape, convexity, or mass density homogeneity, while avoiding combinatorial computational complexity. Our proposed stability heuristic enables our planner to find a solution about 20 times faster when compared to the same algorithm not making use of the heuristic and eight times faster than a state-of-the-art method that uses the traditional sample-and-evaluate approach. Our proposed planner is also more successful in finding stable placements than the five other benchmarked algorithms. Derived from first principles and validated in ten real robot experiments, our planner offers a general and scalable method to tackle the problem of object placement planning with rigid objects.

Motivation

The canonical task of any robot manipulator involves picking and placing objects. While picking has received significant attention from the research community, the second half of the task has been the focus of much less research (i.e. 22 times less according to Elsevier's Scopus database). Unsurprisingly, today's mobile manipulators will often be programmed to only place on horizontal shelves or tables. Even more commonly, they will be programmed to drop objects into bins, avoiding placement planning altogether. Dropping objects into bins is simple in itself but drastically increases the difficulty of retrieving objects later on and requires keeping track of the bin's contents, the walls of the bin concealing much of its contents. How many times have we seemingly lost something that was simply buried under other objects in a bin or a bag?

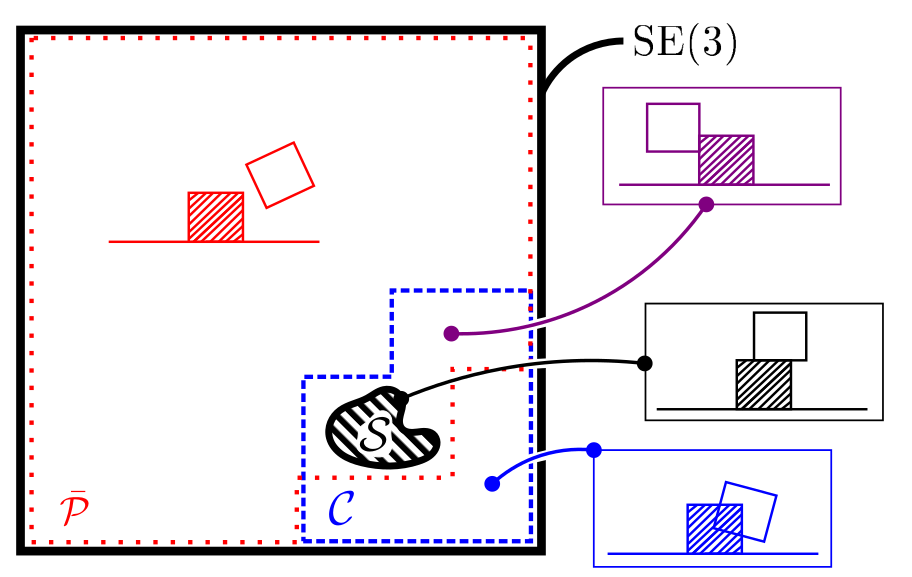

The alternative is to place the object, possibly among other objects, in a stable manner. We typically perform this task when stowing away objects in our homes, in warehouse shelves, in moving trucks, etc. When determining where to place an object (placement planning), we usually want to ensure that no object in the structure (or assembly) slips or falls over. We also might try to minimize the volume of the assembly. Solving this problem requires taking into account the shape, mass, and centre of mass of all objects in the assembly, and to find a pose for the object to be placed that will (1) avoid overlapping with other objects, and (2) results in a stable assembly. Finding a pose meeting these criteria is difficult since a very small subset of all poses will result in a stable assembly.

A possible approach to tackling this problem is to sample a pose, evaluate assembly stability if the object was placed into the selected pose, and repeat until a valid pose is found. This is typically done in a grid-search fashion, where the object is translated and rotated in small increments, and the stability of the assembly is evaluated at each step. Our experiments show that, although this approach can be effective in very simple scenes, it quickly becomes ineffective in more complex scenes.

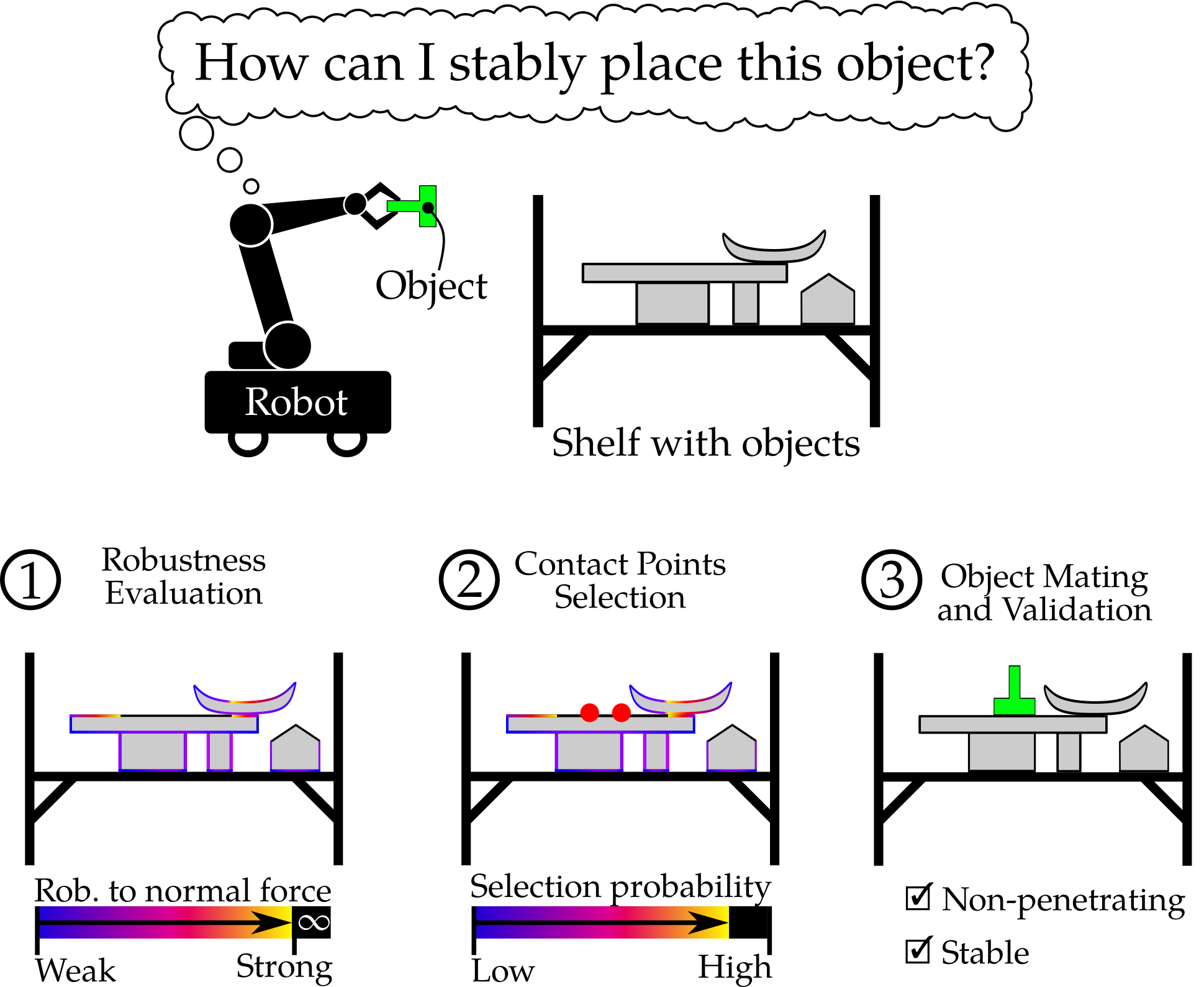

Our Method

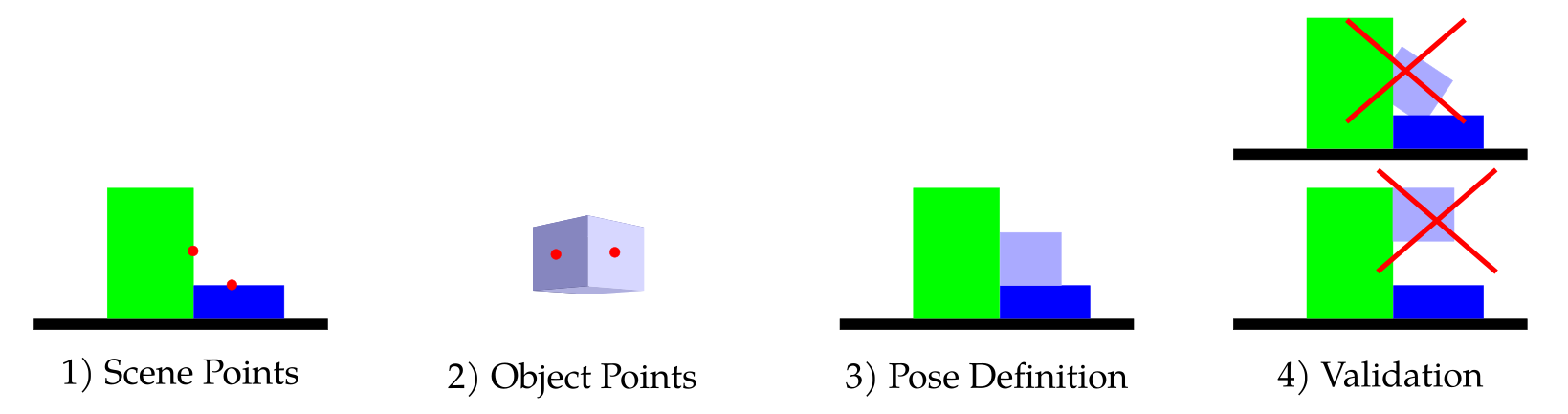

In this work, we propose to reverse the approach to placement planning in order to improve the efficiency of the search. Instead of sampling poses, we sample potential contact points in the scene: by mating two points in the scene with two points on the object, a candidate placement pose is defined. However, our experimental results show that this process alone results in long planning time for scenes with large contact areas. Considering that some contact points are more likely to sustain the weight of the object than others is key in reducing the planning time.

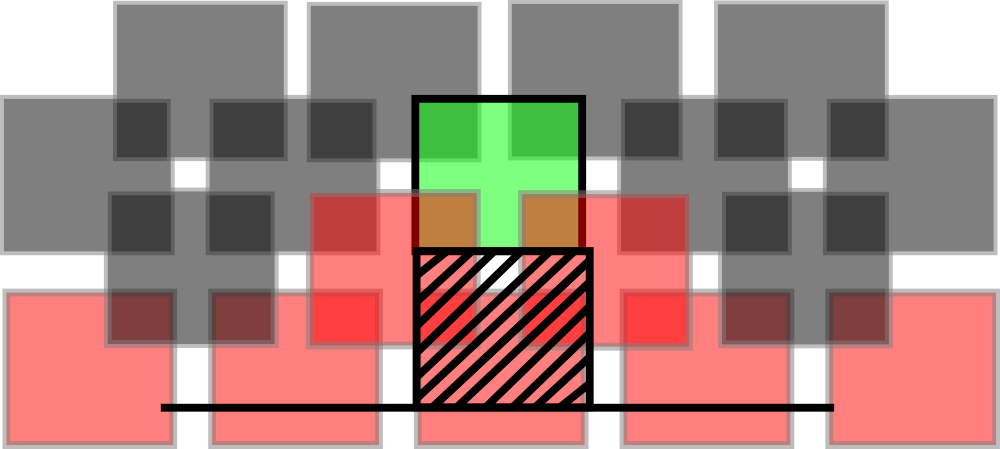

To this end, we propose to base our contact point sampling process on contact point robustness: the maximum amount of force that can be exerted normally to a surface point before any object in the assembly starts to move. In general, evaluating the robustness of an assembly can be computationally expensive due to object interdependency. Hence, for robustness evaluation purposes in the context of our planner, we consider each object in isolation.

At every planning iteration, two points are chosen through robustness weighted random sampling, where the probability of selecting a point is proportional to its robustness. Above a certain value, which decreases over time, the sampling probability is constant such that all points are eventually considered with almost equal probability. On the object to be placed, two points are also selected in a way that favours stability: the points are selected such that the line joining them passes as close as possible to the object's centre of mass.

By mating the two point pairs, and taking the surface normals into account, a pose for the object is defined. Once a potential placement pose is determined, it undergoes a series of checks to ensure that the object does not interpenetrate other objects in the scene and does not destabilize the assembly. A placement pose passing these checks is considered valid. A planner can then repeat the process a number of times before selecting the best placement on the basis of some criterion (e.g, density, median robustness).

Main Results

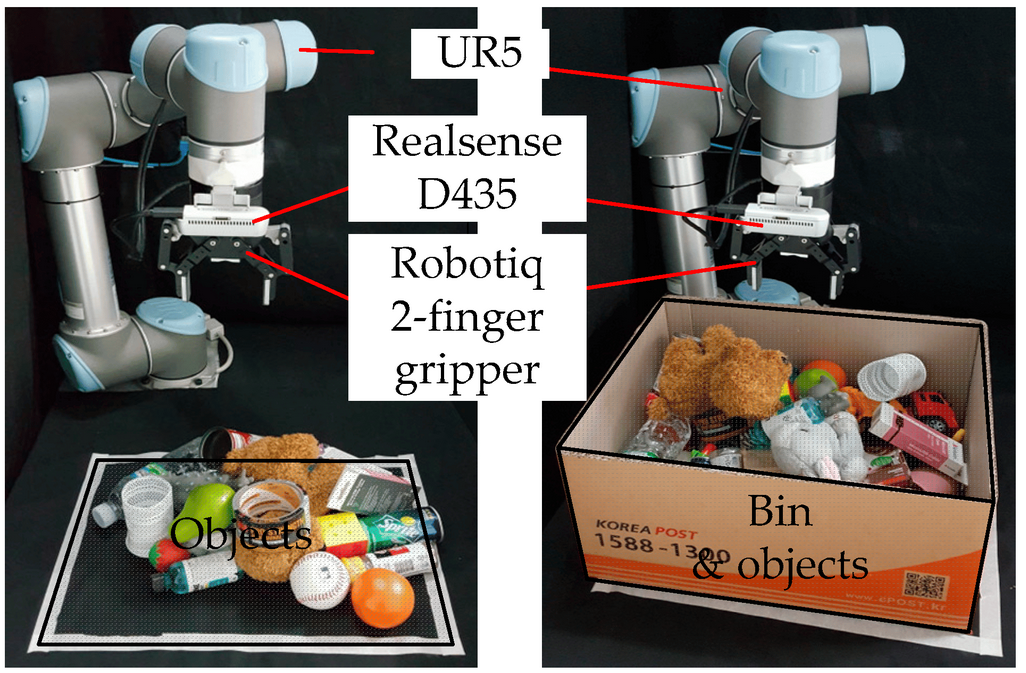

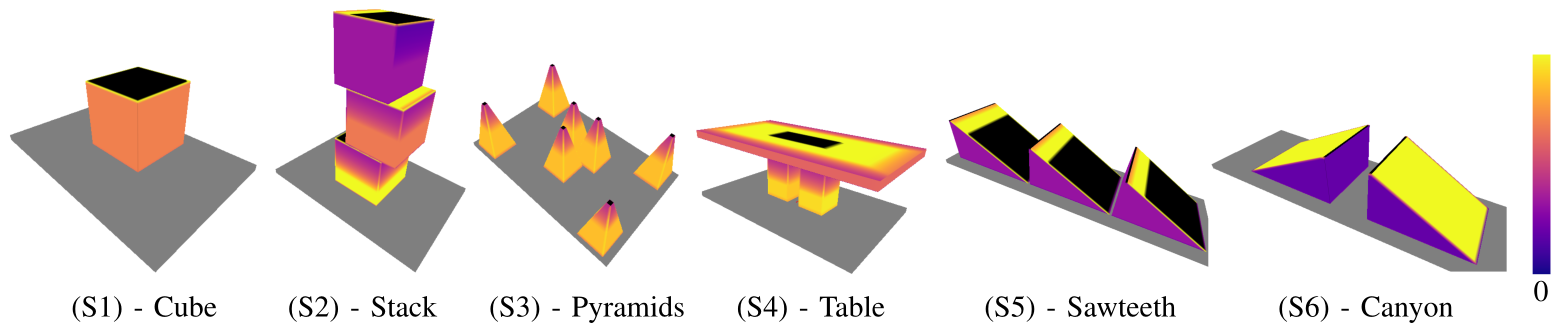

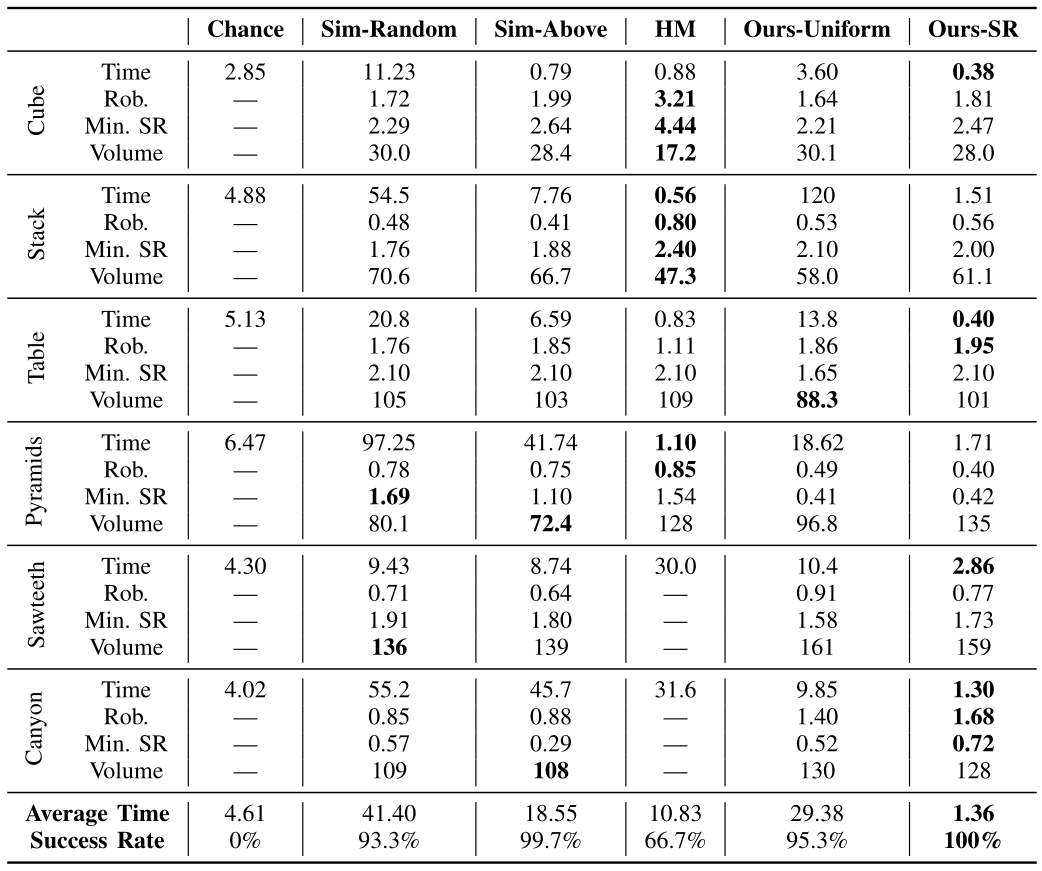

We perform more than 1,500 simulation experiments involving six scenes and six algorithms: our proposed algorithm (Ours-SR), a variation not making use of robustness (Ours-Uniform), a search-and-evaluate algorithm (HM), two algorithms based on dynamics simulations (Sim-Above and Sim-Random), and a random pose selection algorithm (Chance).

Algorithms are compared in terms of planning time, success rate (a maximum of 500 iterations is allowed), the robustness of the resulting assembly, and the packing density.

On average, our proposed method (Ours-SR) is 20 times faster than the same algorithm not making use of robustness (Ours-Uniform), eight times faster than the search-and-evaluate method (HM), and more than 13 times faster than the best simulation-based approach tested. Meanwhile, our method has a higher success rate than any other algorithm tested. Finally, we show that the running time of placement planning scales linearly with the number of vertices of the scene triangular meshes, while robustness computation time grows less than quadratically.

Conclusion

This work defines an inertia-aware object placement planner that can scale to scenes with many objects with no assumption made on object convexity, homogeneous density, or shape. Our algorithm makes use of the object inertial parameters at every step of the process to increase the odds of sampling a stable placement pose and to preserve the assembly’s robustness to external perturbations. We show that the use of our static robustness heuristic greatly increases the odds of sampling a stable placement pose, with a light computational overhead, making the proposed algorithm much faster than other methods.

Citation

@article{2025_Nadeau_Stable,

author = {Philippe Nadeau and Jonathan Kelly},

journal = {IEEE Transactions on Robotics},

title = {Stable Object Placement Planning from Contact Point Robustness},

doi = {10.1109/TRO.2025.3577049},

year = {2025}

}

If you’re interested in learning more, check out the full paper here, or reach out to me directly.